Designing a Symbol Layer

Pascal Getreuer, 2021-10-30 (updated 2025-11-02)

Overview

It’s pretty common in a QMK layout to have a “symbol” layer, for all those symbols that didn’t fit on the base layer, especially with smaller boards.

A lot of effort has gone into optimizing the layout of the alpha keys—Dvorak, Colemak, MTGAP, BEAKL, RSTHD, to name a few (see A guide to alt keyboard layouts). Yet I found relatively little written about how to design a symbol layer. To do something about that, this page discusses some design principles and observations about symbol layers.

Design principles

Symbols are not like alpha characters: they occur less often, and

they tend to occur in isolation or in short bigrams (in C code, things

like # and !=). We can learn nevertheless from

work on optimizing alpha key layouts and apply some of those findings to

symbol layouts:

It’s a good idea to…

put the most used keys on home row and rare keys toward the corners.

avoid the pinkies for keys that are often double tapped (

==,++,//, …). Or you might like a repeat key to circumvent double tapping (QMK repeat key, ZMK repeat key).make common bigrams (

!=,<=,+=,->, …) comfortable to type. Ideally they are inward rolls. An inward roll is a pattern typed on one hand with successive keys moving toward the center of the keyboard (“inward”), like drumming your fingers from pinky to index finger.

And a practicality:

- It’s a good idea to make your layout easy to learn. You won’t use what you forgot!

While each principle above is reasonable for an isolated key, they will easily conflict when getting into the design. Obviously, not all keys can be on the home row and not all bigrams can be inward rolls. We need to make compromises.

Automatic optimization?

There are keyboard layout optimizer tools (like Carpalx, xsznix/keygen, semilin/genkey, and O-X-E-Y/oxeylyzer) that automatically search for a layout that balances many above such considerations, and these could be applied to design a symbol layer. However, automatically designed layouts are notorious for having random-looking hard-to-learn arrangements. It’s also hard with these tools to make a minor adjustment to one key without reshuffling everything else. I think it’s better for these reasons to arrange the symbol keys manually.

Some existing designs

Looking at keymaps in the QMK repo, it is easy to find many existing designs for symbol layers. Here are a few for inspiration:

A reasonable default

This is the symbol layer in the default keymap for the ZSA Moonlander, the Dactyl boards, and probably many others:

(index fingers rest on ) and 4)

The layer is easily learnable. Brackets are neatly organized on the

left hand, and the leftmost two columns are simply the first six number

row symbols in usual order (! @ # $ % ^). The layer manages

to squeeze a numpad onto the right hand. While it’s a well-designed

layer, there is room for improvement, especially for typing common

bigrams.

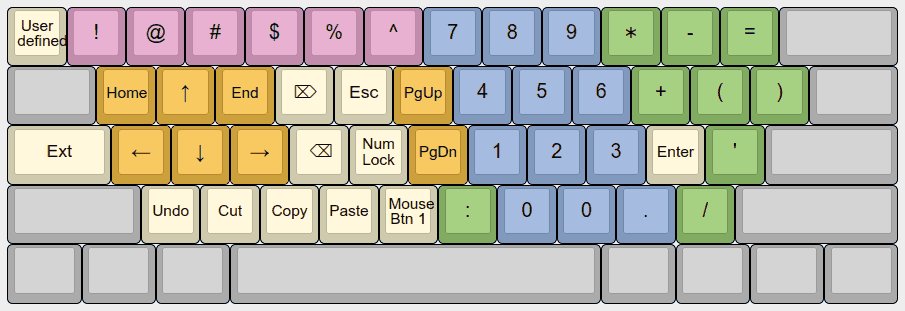

Extend2

Another good general-purpose symbol layer design is Extend2 of DreymaR’s Extend Layer, containing some useful symbols, numpad, navigation keys, and hotkeys.

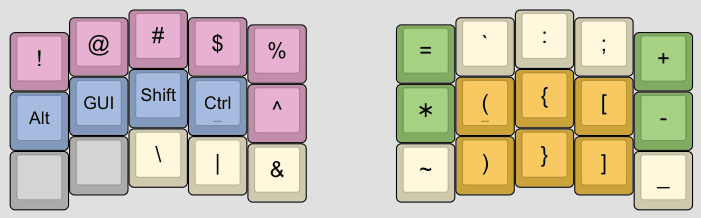

Seniply

SteveP’s Seniply is a 34-key keymap that packs a lot of symbols in one layer, in addition to mods on the left-hand home row:

(index fingers rest on Ctrl and ()

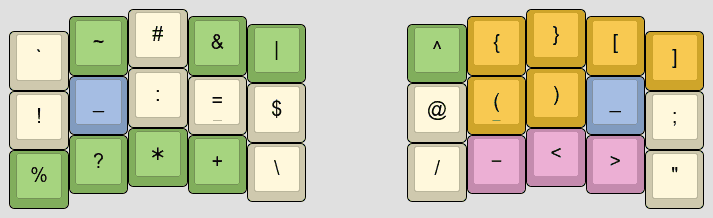

ShelZuuz’s symbol layer

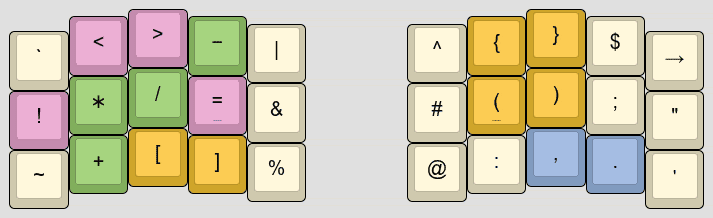

ShelZuuz described this symbol layer, optimized for C++ coding on a 3x5 keyboard:

(index finger rests on = and ()

The symbol layer is entered using layer-tap keys on the base layer, placed symmetrically on the home row ring finger keys (S and L on QWERTY). This is why _ appears twice in the symbol layer, so that _ may be typed by pressing both ring fingers in either order.

Features:

- The very common code trigram

();is an outward roll on the right hand home row. If you prefer inward rolls, ShelZuuz suggests to consider swapping the();{}[]keys to the left hand so that their natural order is the roll order. - The right hand bottom row facilitates arrow bigrams

->and<-. !=is an inward roll.- For easier learning: Keys

{}are stacked directly above(). Keys<>and;are in their usual QWERTY positions. Keys+and\are mirrored by/and-.

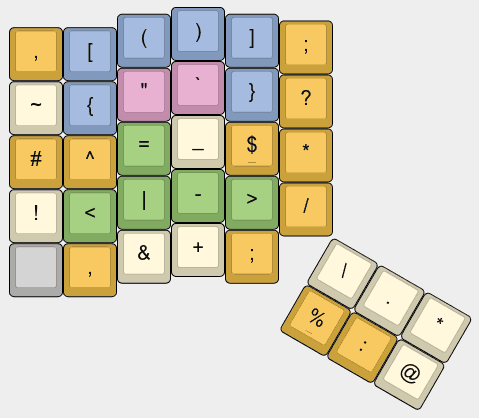

Sunaku’s symbol layer

Sunaku described this as “the crown jewel of my keyboard’s configuration,” resulting from “several hundreds of layout iterations over the last 9 years.” The layer is optimized for programming in Vim.

(index finger rests on $)

Many common syntax bigrams are inward rolls, including

(), [], ->,

<-, !=, <=,

~/. Keys relating to Vim navigation are grouped in pairs,

like ^ $ (start/end of current line) and # *

(search behind/forward). See Sunaku’s

writeup for further details.

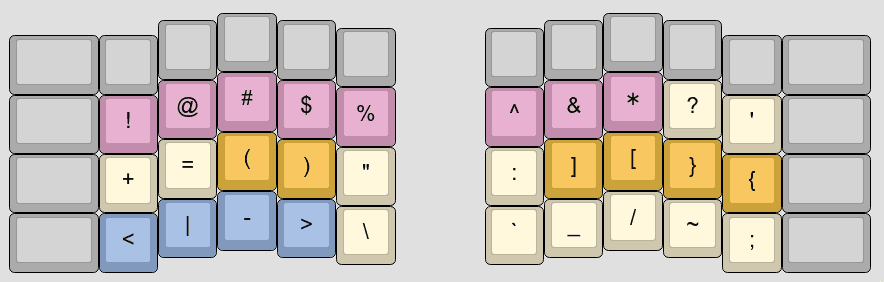

Layer optimized for Elixir code

Dusty Pomerleau posted on elixirforum about a layer optimized for writing Elixir code:

(index fingers rest on ) and ])

As Dusty explains in the linked post, the following bigrams are inward rolls:

- For general programming,

+=,(),[],{} - Specifically for Elixir,

<>,<-,->,|>

BEAKL 15

BEAKL (Balanced Effortless Advanced Keyboard Layout) is a sequence of optimized keyboard layouts, which include symbol layers. Here is the symbol layer for BEAKL 15:

(index fingers rest on ) and {)

Consistent with BEAKL’s philosophy, the layout favors the 3x3 “home block” with the index, middle, and ring fingers, while avoiding the pinky and center columns.

Multi-layer designs

Rather than a symbol layer, another approach is to distribute the symbols across several layers, particularly on smaller keyboards.

Thoughts on keyboard layouts describes a practical 46-key keymap for the Kyria, having symbol keys split across a numpad layer and a symbol layer.

Miryoku is a 36-key keymap. It has a numpad layer, then a symbol layer has the shifted digits in the same positions:

1→!,2→@,3→#, and so on.The default Ferris layout is a 34-key keymap. It has symbols split across two symbol layers. It has a number layer that duplicates some symbols for arithmetic.

Jonas Hietala’s “T-34” layout post describes another 34-key keymap, geared for Rust and Elixir coding. Jonas describes design choices behind it, including thought about symbol bigrams and efficient movement between layers.

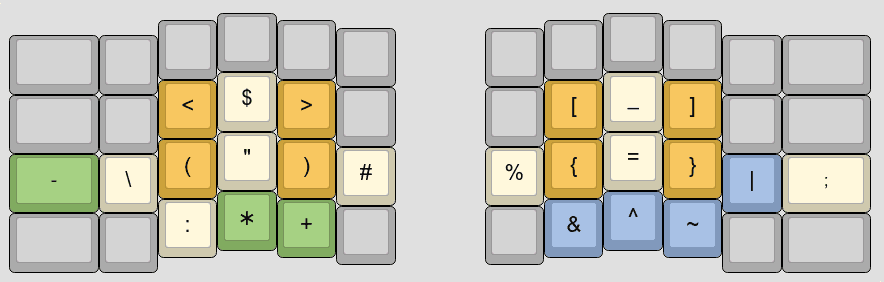

My symbol layer

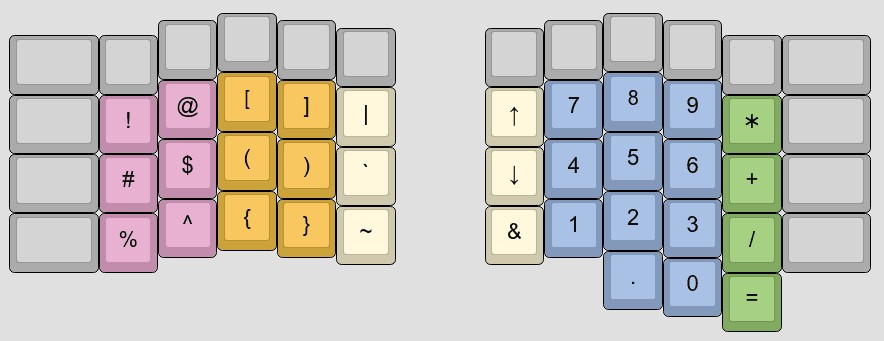

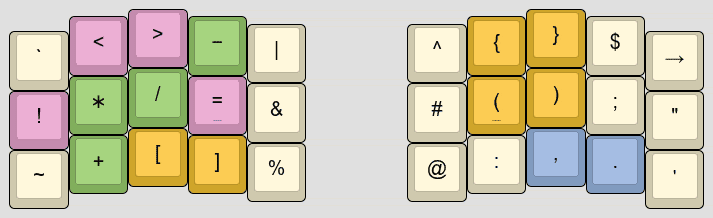

This is my symbol layer, with index fingers resting on = and (.

See my keymap for full context.

I don’t claim it’s the best for you, but that this may be a point of inspiration for optimizing your own symbol layer.

The colors mark groups of related keys: comparisons

! < > =, arithmetic - + / *, brackets

[ ] ( ) { }. To ease layer switching, punctuations

, . appear at the same positions as on my base

layer. The layout is geared for the programming languages I use: mainly

C++, Python, shell, and LaTeX. You should personalize your symbol layer

for you.

Features:

The following are inward rolls:

- Comparisons

!=,<=,>=,~= - Some assignment operators

+=,/=,*= - C comments

/* ... */start with an outward roll and end with an inward roll. - Empty list

[] - Home dir

~/ - Shell syntax

"${variable… and"$(command… - Closing HTML tags

</tag… - Let

<-

- Comparisons

Some other common patterns are outward rolls. That’s not as good as inward rolls, but I find these still pretty comfortable:

();– a very common trigram in C-like languages{}- Arrow operator

-> - Fat arrow

=>

Most symbols are double tapped in some use:

<< == && || **. So pinky keys ` ! ~ → “ ’ are deliberately selected as symbols that aren’t commonly doubled.There is a macro button → for typing Unicode arrows “→” and, when shifted, “⇒.” Since having this key, I frequently find these arrows useful in my writing.

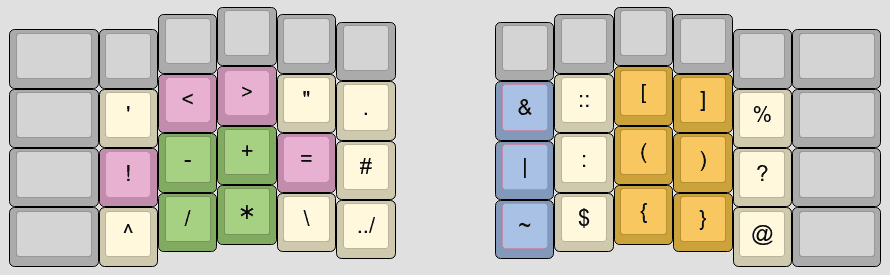

My symbol layer v1 (historical)

I previously shared this earlier version of my symbol layer:

There are a good number of features that I like about it, and indeed my current symbol layer has many similarities. Motivations in revising it were:

- This earlier layout is awkward for HTML. Closing tags

</is a clumsy same-finger bigram, and HTML comments<!-- ... -->are awkward to type. - I want

();as a roll, like ShelZuuz’s layer, since this syntax appears so much in code. - I wanted , . in the same positions as the base layer to ease layer switching.

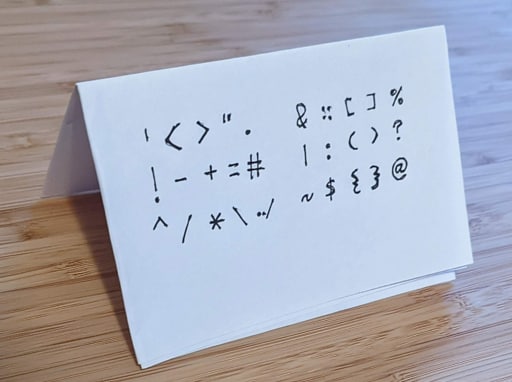

Learning your symbol layer

As I mentioned, you won’t use keys that you forgot about. It’s important to learn your keyboard layers.

Whenever I change a keyboard layer, something that works for me is to write the layer on a slip of paper and put it below my monitor. The act of writing out the layer helps reinforce it in my mind, and the paper is there to refer to when I need a reminder. After a few weeks, I have it memorized and can throw out the paper.

Another way to learn is with typing practice. Try out your symbol layer on typingclub.com’s symbol practice or type-fu.com’s code lesson.

Symbol character frequencies

This section is on measuring character frequencies, which helps optimize the layout for the programming languages you use. Some symbols occur much more often than others. It’s helpful to know the distribution so that we can prioritize the layout for more frequent symbols.

I counted how often each symbol occurs in my own files. I found that this depends greatly on what kind of file it is. Below are character frequencies counted on six different kinds of text, each column counted on at least 40K of data. Units are percentages. “Prose” is a mix of email and other plain text files. “Mixed” is a mixed corpus.

Prose C/C++ Python Shell LaTeX Mixed

#1 . 1.249 _ 1.369 _ 2.213 " 2.792 \ 2.254 , 1.416

#2 , 0.952 * 1.238 . 2.183 - 2.430 { 1.327 . 1.067

#3 1 0.743 , 1.200 , 1.428 $ 1.464 } 1.326 " 0.529

#4 0 0.713 ) 1.151 ) 1.248 0 1.386 . 0.932 _ 0.497

#5 - 0.633 ( 1.151 ( 1.246 = 1.386 $ 0.800 ) 0.396

#6 2 0.514 . 1.037 ' 0.844 1 1.333 , 0.754 ( 0.396

#7 ) 0.487 / 0.991 " 0.784 _ 1.250 _ 0.454 - 0.362

#8 ( 0.486 0 0.938 = 0.780 / 1.219 ) 0.383 * 0.343

#9 6 0.396 ; 0.909 0 0.692 ] 1.095 ( 0.372 ' 0.335

#10 4 0.394 - 0.689 : 0.663 [ 1.095 1 0.370 ; 0.317

#11 / 0.360 1 0.643 1 0.422 . 0.937 0 0.361 0 0.315

#12 8 0.306 = 0.589 2 0.373 # 0.898 2 0.344 / 0.290

#13 5 0.298 2 0.554 # 0.336 2 0.879 - 0.285 1 0.223

#14 3 0.281 3 0.361 [ 0.332 \ 0.823 : 0.232 = 0.210

#15 + 0.274 : 0.336 ] 0.329 ; 0.748 % 0.212 2 0.191

#16 [ 0.246 4 0.321 - 0.303 : 0.658 ^ 0.194 : 0.162

#17 ] 0.246 8 0.311 / 0.184 ) 0.653 ~ 0.176 \ 0.150

#18 9 0.231 { 0.291 3 0.171 ( 0.493 = 0.152 { 0.136

#19 7 0.219 } 0.291 * 0.162 , 0.476 / 0.141 } 0.136

#20 : 0.210 5 0.288 5 0.141 3 0.473 [ 0.131 3 0.115

#21 = 0.191 9 0.287 4 0.136 6 0.466 ] 0.128 4 0.101

#22 _ 0.168 6 0.286 > 0.110 4 0.422 5 0.128 [ 0.101

#23 | 0.137 + 0.282 6 0.108 ' 0.422 3 0.113 ] 0.100

#24 ' 0.098 > 0.272 ` 0.081 5 0.362 & 0.110 5 0.093

#25 " 0.070 < 0.264 8 0.076 9 0.279 9 0.095 8 0.093

#26 * 0.064 [ 0.262 + 0.076 8 0.260 7 0.094 6 0.090

#27 < 0.031 ] 0.262 7 0.072 7 0.250 4 0.088 ! 0.089

#28 ? 0.020 " 0.251 \ 0.057 | 0.248 6 0.087 9 0.087

#29 @ 0.018 7 0.247 < 0.057 % 0.204 + 0.075 + 0.083

#30 ~ 0.017 \ 0.186 { 0.057 } 0.187 8 0.071 > 0.079Caveat: What we actually care about are keys

typed. But considering editor hotkeys, that’s not necessarily

the same as characters written, which is what the above counts.

For instance in Vim, many symbol keys are hotkeys in normal mode, like

/ for search.

Some observations from these stats:

.and,are extremely frequent. You probably want them as unshifted keys on the base layer. In code,_is also near the top, so I put a ∗ key on my base layer.Digits

0 1 2are more frequent than the other digits, an observation known as Benford’s law. They are also more frequent than most other symbols. But I wouldn’t put0 1 2on a different layer than3 4 5 6 7 8 9—typing numbers would then require too much layer switching. My conclusion is digits better go on the base layer, even for coding, contrary to “programmer” layout variants.For each programming language, the commenting characters in that language are frequent:

/* */in C,#in Python and shell,%in LaTeX.<and>are relatively uncommon in all contexts, ranking #24 and later, yet it is standard to have them on the base layer by shifting the , and . keys. A good idea is to replace Shift + , with!and Shift + . with?. See my custom shift keys post for a method of doing that.

You can count character frequencies in your own files with this Python script: count_chars.py. The script reads the specified files and counts how often symbol characters occur. Use it like

python3 count_chars.py input.txtOr to compute counts across multiple files, do

python3 count_chars.py file1.cpp file2.py file3.shConclusion

We can apply principles from alpha key layout optimization to designing good symbol layers. The frequency of different symbol characters and bigrams depends a lot on what kind of text is being typed. So it makes sense to personalize your symbol layer to your needs. I hope this post gave some useful ideas on how to do that.